There was much hullabaloo over a post written by Slate economics columnist Matt Yglesias earlier last week about why America has too many banks. While many have written pieces that argue against this premise, I feel it necessary to present my proverbial two cents.

The concluding tag line on my column here at Pocket Full of Liberty is free markets are better markets. The reason that I strongly believe this is true is because I believe in the virtue of competition. Competition is good for consumers. Competition is what lowers prices and provides better products and services through innovation. Competition also forces competitors to remain sharp.

It’s easy to laugh at government inefficiency at places like the Department of Motor Vehicles. The problem is that state government has a monopoly on issuing drivers’ licenses. You have to go to the DMV to get a license. There is no profit motive at the DMV and no real repercussions for what consumers would deem to be poor service. Because of this, there is no incentive to be a “lean, mean, well-oiled DMV machine.”

Compare and contrast this with the United States Postal Service. Similarly, the post office is inefficient and bloated because there is no competition for letter delivery. When it comes to package services, however, there is competition from UPS, FedEx, DHL, and other couriers. The post office is forced to adapt by offering new and competitive package services. If they do not do that, they will fail. This, perhaps, is why the USPS teamed up with Amazon.com with respect to Sunday package delivery. It is an interesting innovation and may lead to the USPS making a profit on something. Time will tell.

But I digress. On to Mr. Yglesias’ post, which suggests that America has too many banks.

With respect to the idea that “fewer banks are a good thing,” I generally find it odd that those on the left would support such a notion. Typically (and, of course, at the risk of generalizing) folks on the left view mergers and acquisitions with some suspicion to say the least. Indeed, this was true when Exxon and Mobil merged and subsequently bought out XTO Energy, and more recently when AT&T failed in its bid to buy out T-Mobile. There seems to be some support of mergers between two “weaker” competitors, rather than a “stronger” competitor buying a weaker one.

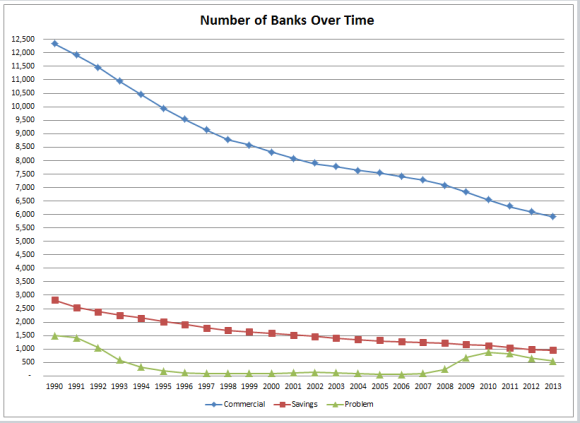

Mish Shedlock puts up some nice charts (courtesy of Tim Wallace) on his site, which show the declining number of banks since 1990 — roughly when the last serious banking crisis was ongoing (the Savings & Loan crisis).

In 1990, there were more than 12,000 commercial banks in the United States. Now that number has nearly been cut in half due to a number of reasons, including failure and merger.

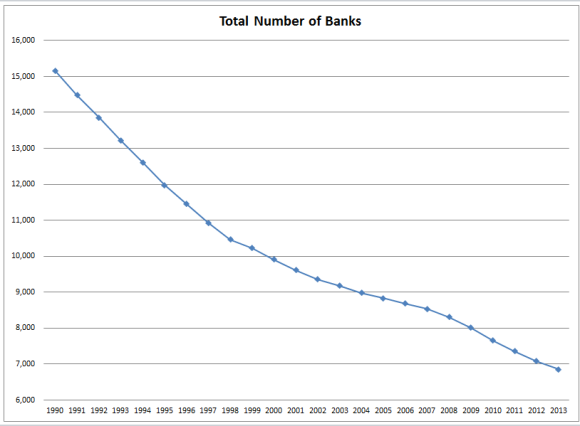

Here, you can see the number of banks continues on a steady decline since 1990.

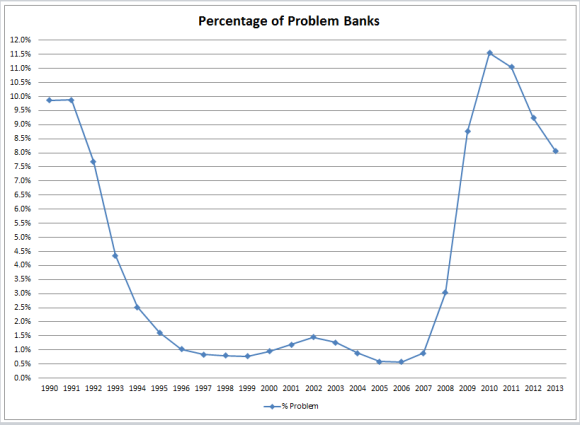

The number of problem banks has been at elevated levels as well. This is not a good thing, especially when the total number of banks is declining. The ratio of problem banks to non-problem banks remains very elevated.

The problems that Yglesias outlines with the number of banks (specifically “microbanks”) are as follows:

- They are poorly managed.

- They can’t be regulated.

- They can’t compete.

Are small banks poorly managed? No. Actually, many small banks are better managed than some of the big banks. Although this article is dated, it expresses a very important concept. Banking should be boring.

“Banking should not be exciting,” said Clay W. Ewing, president of retail financial services at German American Bancorp, a community bank in Jasper. “If banking gets exciting, there is something wrong with it.”

It is an ethos squarely at odds with the risk-addicted style of megabanks, like Citigroup and Bank of America, that trafficked in the subprime mortgages and complex financial products that helped drive the country into the grimmest recession in decades.

The idea for many of these smaller banks is simple. They focus on not losing money, which many (including Uncle Warren) say is the key to making money. In other words, the smaller banks lend money out prudently and at a higher rate than it costs to bring in the funds (i.e., deposits) and avoid excessive risk through leverage. They may make less profit in the short-term, but they avoid the dangers associated with excessive risk.

Forget “too big to fail.” These banks consider themselves too small to risk embarrassment. They are run by people who grew up in the towns where they work, and their main fear is getting into a financial jam that will shame them in the eyes of their neighbors.

The steep profits earned by national banks didn’t turn their heads in the last decade because they were inherently skeptical of double-digit growth rates.

“We like a nice, gentle, upward slope,” said Donald E. Goetz, the president of DeMotte State Bank, an 11-branch operation in the northwest part of Indiana.

“This kind of growth, like you see in the stock market” — Mr. Goetz ran his hand through the air, tracing the shape of a mountain range — “that doesn’t interest us.”

Obviously, not all small banks are well-managed. But the idea that a bank is better managed simply because it is bigger or has offices in Manhattan is naive. Microbanks generally do not engage in subprime lending as this article from 2009 suggests. Because of this they are not the culprits behind the decline in the housing market and subsequent economic downturn.

Are small banks regulated? Of course they are. To suggest otherwise is simply incorrect. All banks are subject to a plethora of regulations on the state and federal level. As Sean Davis points out at The Federalist:

According to the Independent Community Bankers of America, the industry’s trade representative, the federal government had, as of February of 2013, issued or proposed 900 new regulations since 2007. And if that source strikes you as a bit too biased, the Government Accountability Office wrote in a September 2012 study that regulations required by seven of Dodd-Frank’s 16 titles would significantly affect community banks.The other problem with regulation is that generally te affect smaller banks in a more disproportionate manner than megabanks. Indeed, megabanks have the resources and size to adapt to the regulations (which some argue that the megabanks wrote themselves through lobbying). The Federal Reserve notes that:

The other problem with regulations is that they tend to disproportionately affect smaller banks versus megabanks. Indeed, megabanks have the resources and size to adapt to the regulations (which some argue that the megabanks wrote themselves through lobbying). The Federal Reserve notes that:

As a Federal Reserve staff study of the costs of bank regulation explains, “Higher average regulatory costs at low levels of output may inhibit the entry of new firms into banking or may stimulate consolidation of the industry into fewer, large banks.”

In other words, ironically, regulations can lead to more “too big to fail” banks and to fewer banks overall. This is (in very rough form) the idea behind Robert Bork’s “The Anti-Trust Paradox.”

I’ve discussed regulatory costs as a “stealth tax” on business. Like our progressive friends suggest, the richer can “afford” to pay more. Likewise, for example, the megabanks can afford to pay the compliance costs associated with Dodd-Frank, while smaller banks may not. In other words, regulation drives banks out of business:

Big banks can afford the added costs, even though the biggest eight are expected to shell out a combined $35 billion a year to comply with Dodd-Frank. But they’re wiping out profits for small banks, already squeezed by lower interest rates.

Cape Cod Five Cents Savings Bank, a Massachusetts thrift, says the law has added three layers of compliance, forcing it to hire outside help. Tiny United Southern Bank in Kentucky has had to hire 15 more employees to help comply with the regulations.

Of the 322 small banks recently surveyed by the Kansas City Federal Reserve, 91% said they were laboring under higher training and software costs due to Dodd-Frank. The Minneapolis Fed, moreover, figures that hiring two additional bank workers to comply with the new rules would force fully a third of smaller banks to operate in the red.

Shelter Financial Bank in Missouri was forced to close last year after figuring Dodd-Frank would add $1 million in annual costs, making it unprofitable.

Small banks are absolutely regulated. Some are regulated out of business — much like the middle class.

As for Yglesias’ final point, that small banks “can’t compete,” this seems like a rather amorphous assertion. What does “compete” mean? If “compete” means “make more money than the megabanks,” he’s probably right.

But there are several reasons why smaller banks are better than megabanks. For example:

1. Smaller banks may be more willing to lend to smaller business.

PFoL Executive Editor Amy Otto suggested this to me and it makes sense. A small, local business may have an easier time getting a loan from a small bank rather than walking into an impersonal megabank. Mercatus also agrees:

Community banks have profited from using “soft information” not available to their larger counterparts. As Marsh and Norman explain, “In contrast to the complex financial modeling large banks use, community bankers’ specialized knowledge of the customer and their local market presence allows underwriting decisions to be based on nonstandard soft data like the customer’s character and ability to manage in the local economy.” Rules adopted by the CFPB under Dodd-Frank do not leave much room for the consideration of such soft information. As George Mason University law professor Todd Zywicki explains, the CFPB’s “one-size-fits-all regulatory approach tends to thus disadvantage those banks that compete on margins such as customer service while favoring those with the lowest costs, big banks that offer economies of scale and lower capital market costs.”

If you know your banker personally, he may be able to use this “soft information” to make a loan to you which a megabank would not (or could not) consider. This may not necessarily be a “riskier” loan, but merely one where such soft information was the factor that tipped the scales.

2. Not all consumers are the same.

One-size-fits-all is not necessarily the best way to go. We are seeing this with Obamacare where plans are required to offer nursing coverage to males of retiring age. While this may be a good idea for some, it really just raises costs, wastes money, and prices people out of the market. Likewise “one-size-fits-all” banking is bad:

The needs of homogenous consumers can be met with homogenous products, but the assumption that consumers are homogenous is wrong. Community banks’ practice of getting to know their customers and tailoring products to their needs is at odds with the Dodd-Frank version of customer protection.

Not everyone needs the same banking product. Banks that know their communities (and small locally-based banks know their communities better than corporate conglomerates) will offer the type of banking products that the community needs or wants. Why shouldn’t local banks be able to do that?

3. More competition is a good thing.

While small banks may not be able to compete with megabanks in terms of revenue (in absolute dollars) or reach, they are able to compete with their knowledge of their communities. This provides them with a competitive advantage in this regard. Again, the consumer seeking a banking product may, depending on his need, be able to have it satisfied by a small bank. This consumer should be given the freedom to make such a choice. Competition is a good thing. Let the consumers make the choice.

4. More banks = less “too big to fail” banks.

There are reams that could be written on this topic, but I will approach it on a very cursory level. Yglesias suggests that a dozen large banks would be better. However, some would argue that as banks get bigger, they become more reliant on government guarantees because they’ve become “too big to fail” — or of such systemic importance that their survival is necessary. Because of this, the government needs to guarantee their survival. This creates a major vicious cycle, because the government backstop creates an incentive for such megabanks to take on as much risk as they think they can handle. If they succeed, they profit. If they fail… no, they can’t fail.

Once again, when competitive incentives disappear, we have systemic problems. Like the DMV, a “too big to fail” bank has no repercussions from bad behavior. If you really want safer banks and more competition, then the implicit or explicit backstop of “too big to fail” needs to be removed. More banks would help ensure this.

As always, free markets are better markets.

* * *

This week, on Thursday, be on the lookout for jobless claims (estimated at 325k) and retail sales (+0.6% month over month, +0.3% excluding auto sales). I think retail sales and reports will move the market more than jobless claims because of the holiday season. We are also roughly a week away from the December Fed meeting, where some think that the taper will begin. Others (myself included) think that the taper won’t begin until early 2014 at the earliest. More on this soon.

Have a great week!