The situation in Syria has divided those on the Right. One side sees no interest for the U.S. there. No matter which side wins, we are no better off and our involvement will cost American lives. The other side argues that we should get involved because of the humanitarian disaster there — over 100,000 dead — and the use of chemical weapons by the Assad regime. Some even go so far as to say that rather than aid any side, the U.S. and others should occupy Syria, depose the regime, and replace it with a technocrat who can provide stability and improve the governing situation.

I see all points of view in this case. I do not think that the U.S. has an interest in every situation abroad nor that there is nothing to be said for the idea that we are responsible as a superpower. I attempt to take each case on its merits, neither prescribing to an interventionist or non-interventionist philosophy. That means (I must admit) that in the case of Syria, I only made up my mind last week.

As with virtually every conflict in which we consider action, there are no good alternatives — only less bad ones. That is especially true in this case. There are approximately five different general policies that have been advanced concerning Syria:

- Depose and replace Assad

- Aid the rebels, but leave the deposing and replacing to them

- Aid the Assad regime

- Launch some cruise missiles to prolong the conflict, to make the Assad regime stop using chemical weapons, or to save Obama’s face — depending on who you are

- Non-intervention

Leaving the first and last options for later, let’s examine the other three. The most obviously bad option is to aid the Assad regime. He is supported by Iran and has been on the State Department’s State Sponsor of Terrorism list since 1979. Rather than actively promote terror nowadays, the Syrian regime tacitly promotes it by doing nothing to stop the shipment of supplies and soldiers to Hezbollah through the country into south Lebanon — where Hezbollah destabilizes the situation there (even more so) and chronically launches attacks into Israel.

The conservative argument for supporting Assad is that what replaces him might be worse and that while al-Qaeda has attacked us directly on our soil, Hezbollah is regional in its aims. But as bad as al-Qaeda in Syria sounds, the Iran (and Russia) backed terror-supporting Assad doesn’t sound so much better to spend American blood to back him up. Furthermore, while Hezbollah confines its interests to the Levant, Iran is a global threat.

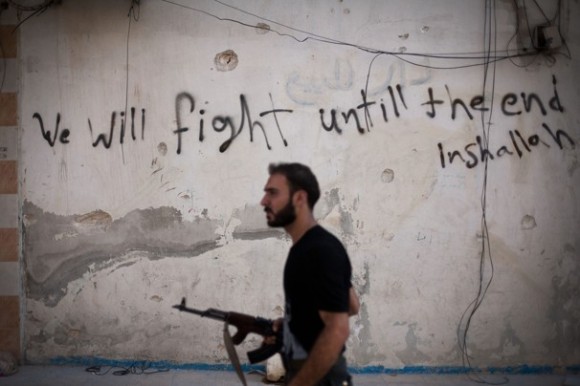

Aiding the rebels is no better. Seven of the nine rebel groups are strongly suspected of having “significant ties” to al-Qaeda. Do we really believe that the same President Obama — who dithered up to now on what to do in Syria, has spoken favorably of Muslim Brotherhood-led revolutions, and who failed to do anything in support of the Green Revolution against the Iranian regime — is really going to pick one or both of the so-called moderate groups and dexterously aid their rise to power over the other seven?

There is an argument that involvement in their favor when the rebellion was more moderate may have resulted in a moderate regime in Syria. But that time has passed.

Third, we could chuck some cruise missiles into the conflict. It certainly wouldn’t cost much compared to other plans. Putting aside the fact that Obama’s prime reason for proposing this plan is to save face for his otherwise unsubstantiated red line, it is argued that by choosing this route we could either stop the use of chemical weapons or prolong the conflict so that, in effect, both sides lose.

Still, more than one foreign policy expert finds this policy to be too little, too late — such as Elliot Abrams for the Council on Foreign Relations and David Rothkopf with Foreign Policy. The latter does argue that a similar tactic of bombings targeting economic assets “was an example of successful but limited use of air power without ground support that advanced a specific goal — in that case, the withdrawal of Yugoslav forces from Kosovo.” However, Stratfor’s Robert Kaplan lays out many differences between the situation in Kosovo and the present one in Syria, not the least of which is Iran and Russia’s backing of Assad.

So it’s all or nothing. Full occupation, deposition and replacement with the help of a coalition (which will likely not include Great Britain) or non-involvement.

For three reasons, I oppose U.S. involvement in Syria.*

The first is why Robert Kaplan hesitates to compare Syria and Kosovo: Russian and Iranian backing. Don’t get me wrong, I have no problem taking on one or both of them in the right context. But I believe that their support will make this occupation even more difficult than our experience in Iraq.

Furthermore, unlike Iraq, the opposition forces seem much less likely to desire a transformation to a Western-friendly, moderate, and modern nation — and much more likely to keep Syria in the past with support of Islamic extremism. Even with a technocrat chosen by a coalition, such a transformation will be extremely difficult without a population in favor of it. I’m not convinced we have one in Syria.

Finally, and most importantly, I don’t think the Obama administration can pull off this or any policy of major intervention. The president is simply not wise, understanding, experienced, or interested enough. Beyond the aforementioned poor choices of support he has made in the past, Obama is reported to have played cards throughout the raid that killed Osama bin Laden, saying “I can’t watch this entire thing.” He is still unaccounted for during the Benghazi strike. This would be difficult for the Bush administration to pull off. I don’t trust Obama to see this through wisely to the end.

To give credit where credit is due, others have said the same thing. The American Spectator’s Andrew Wilson says, “I believe that the Obama administration will be incapable of taking decisive action — either in destroying stockpiles of chemical weapons or in removing the Assad regime.” Ricochet’s Arthur Herman asks, “Do we want this president, Barack Obama, making any decisions where American interests are at stake — and where Americans, and possibly many others, may die?” His answer “is an emphatic no.” He gives reasons similar to Wilson’s and mine here.

A quick note on the humanitarian crisis there: 100,000 deaths is a terrible atrocity that I would like to stop. However, I don’t see a policy that will quickly end the bloodshed. Additionally, it is one thing when it is the result of unprovoked ethnic cleansing and another thing entirely when it is a consequence of a protest-turned-rebellion-turned-civil-war along with the collateral damage that always accompanies war.

I simply don’t see any intervention made by the U.S. in Syria as resulting in a net gain for us. Nor will we do anything more than put a band aid on the real problems there. Unless and until another option presents itself, I will have to oppose any American involvement there for the foreseeable future.

*For the best argument in favor of a proactive “full occupation, deposition and replacement” policy I’ve read, see Matt Parlmer’s post here.